The Trust Problem That Slows Digital Transformation

Tension between business executives and IT professionals can be managed in ways that build respect for each other’s capabilities — and open new doors in the process.

Topics

Pick up any industry or professional publication and you’ll be deluged with articles extolling the value of digital transformation. Supporters tout new capabilities as do-or-die. “All companies must become tech companies” is a common refrain. “Organizations that speed their decision intelligence capabilities will survive, and those that don’t will fail” is another.

Count me among those who are excited for this messaging. I see enormous potential for new digital capabilities to improve business performance, create more satisfying jobs, and solve some long-standing issues that have proven beyond the reach of methods typically employed today.

Still, adaptation and change remain challenges for most companies. All change, even the smallest, depends on trust. As George Shultz, U.S. secretary of state during the Reagan administration, famously observed late in life, “Trust is the coin of the realm.” When trust was in the room, he wrote, good things happened. Without trust, they did not.

The problem is that, too often, business departments simply do not trust their IT counterparts. Until this problem is tackled and solved, critical initiatives around digital transformation will stall.

IT Is in a Tough Spot

When the topic of trust first came onto my radar some years ago, I began, somewhat sheepishly, to ask people about it. I was surprised by how negative so many businesspeople felt about their IT departments. I heard comments such as, “We really can’t trust them to do anything important,” and “They are the least liked group in my company.” Even during the early months of the pandemic — when IT teams scrambled to bring videoconferencing, online ordering, and other innovations to operations to help save the day — such comments persisted. (One point of light was that while comments would often denigrate departments as a whole, individual IT team members were often appreciated.)

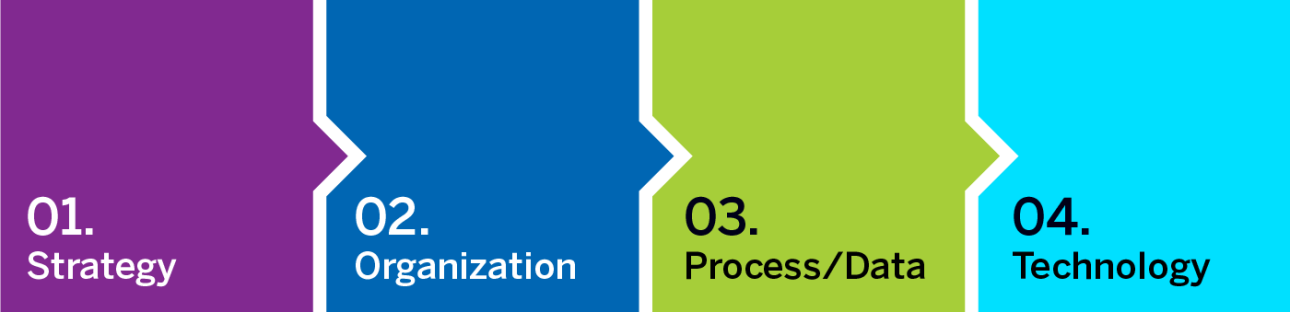

Why is trust so low? I find the following figure, which I’ve adapted from John Roberts’ 2004 classic book The Modern Firm, helpful in understanding how mistrust between business leaders and IT professionals grows and festers.

Source: Adapted from John Roberts’ The Modern Firm

The idea is that a company (or any department or team) should start at Step 1, by sorting out what it wants to achieve — its strategy — and its business objectives. This makes sense: You have to know where you want to go before you start moving. Next, in Step 2, participants should sketch out the organizational capabilities they need to execute that strategy, including people, structure, culture, and management routines. For Step 3, leaders should define the processes and data they (and the project overall) will need to do the work. Finally, during Step 4, they should apply the technology necessary to increase scale and decrease unit cost.

Most of the problems and the ensuing lack of trust I’ve witnessed stems from not doing the early steps well, getting them out of order, or stumbling over confusion about who is supposed to do what.

Issues are often rooted in Step 1, when business objectives are unclear. “Executives need to address two questions right up front,” says Bob Palermo, a consultant and former vice president at Shell. “Do they wish to employ standard processes — or is each business unit left to do as it sees fit? And do they wish to integrate functions tightly together — or let them fend for themselves?” Left unanswered, business silos push for technical solutions that meet their specific needs, meaning less standardization and integration than is eventually required. The result is “systems that don’t talk.” And people blame IT.

Problems also often come up at Step 3, with IT asked to do the work of defining the necessary processes and data. This is the natural province of the business side of an organization and outside IT’s domain of expertise. It’s tough for IT teams to refuse such assignments, but they are also not likely to produce good results. Many things can go wrong, including the automation of a poorly defined process, the reuse of unclean data, and an insufficient integration of data with the project’s needs.

It is unfair, unreasonable, and unwise to expect IT to define processes, clean up data it did not create, or have the nuanced understanding to know how to best integrate data across platforms and databases. But IT often gets blamed for poor results stemming from this crucial step. And mistrust grows.

Hype exacerbates these issues by making it appear that digital transformation is easy. The reality is that transformation requires a hard-to-assemble combination of change management, processes, data, and technical talent.

Issues sometimes also arise when proponents of a great new technology push to reverse engineer the process, starting first with the technology (Step 4) and working backward to a strategy. This reasoning is along the lines of “If we build it, they will come,” to borrow a theme from the Kevin Costner movie Field of Dreams. But while blind hope may be rewarded in the movies, it rarely is in real life.

New technologies can disrupt, of course. But even the most potentially disruptive rarely circumvent the steps above. Blockchain, which has garnered considerable hype for a dozen years, provides a great example. As University of Arkansas professors Mary Lacity (of the Center for Blockchain Excellence at the Sam M. Walton College of Business) and Remko Van Hoek explore fully, those who’ve succeeded with the technology are business-led and have focused on specific problems (Step 1), assembled broad coalitions of participants (Step 2), and dealt with data issues (Step 3).

How to Build Trust

Building trust doesn’t happen overnight, but there are ways company leaders can get teams to better respect each other’s capabilities and begin working together in more productive ways. Here are four:

Frame IT’s relationship to the business as supplier to customer. The logical first step to breaking the cycle of unreasonable expectations leading to failure and mistrust is to better define each side’s roles. I think the best model is IT as the supplier and the business as the customer.

Each should honestly evaluate its performance — because in most cases both need to do better. The business must become a better customer, which means holding up its end in Steps 1, 2, and 3. In particular, the business must provide clearer direction, better staff its portions of the work, develop clearer requirements, and work with IT to sort out reasonable expectations.

For its part, IT must better acknowledge business concerns as a savvy supplier would, from cost overruns to slow delivery to lack of responsiveness. IT must also learn how to push back when any of the inputs it needs to be effective (from Steps 1 through 3) prove inadequate. For example, businesspeople may not understand what constitutes “clear requirements.”

Find common ground over data. IT and business groups both agree that data is important, though each often assumes the other must play the lead role. Upon reflection, most agree that the business groups should define and create most data (as part of Step 3) and bear principal responsibility for it. But there are limits. For example, businesspeople are ill prepared to create the logical data model needed to define a database system. Many open-ended discussions will be needed on who is responsible for what when it comes to quality, security, metadata, common language, data architecture, and storage.

Socialize. This recommendation is the simplest yet may be the most profound. I call it “Let’s do lunch.” The reality is that people work more effectively together when they know a bit about each other, their backgrounds, their families, and their interests. People at all levels on both sides need to make time to get to know one another.

Start with the basics and grow from there. Business leaders and their IT counterparts should take on more difficult issues and opportunities only as their mutual level of trust grows, as the customer-supplier model has limitations. For example, almost everyone agrees that “ensuring our systems talk” and “keeping technical debt low” are great concepts that will make it easier to work across silos and lower costs. And sooner or later, companies must do the work to make such concepts a reality. But companies should wait to address them until trust in IT has grown, they can align departments’ interests, assemble the team needed to complete the work, and commit to a long-term investment.

In building and reinforcing trust, don’t expect miracles. Lack of trust may have infected your organization for a long time. It sn’t doing anyone any good, and it’s an important problem to tackle if your organization is to have any chance of successfully implementing digital transformation projects. IT and business relationships are essential, and making this investment is worth the effort.